Photo caption above: Eddie Sauter giving the downbeat to the Night Gallery orchestra. Below: Willard Alexander agency publicity photo of Eddie Sauter in the 1950s.

Any account of Eddie Sauter's contributions to music should include his lifelong study of music and composition.

Adopted at an early age into the Sauter family, Eddie's blood brother, Stanley Meyers, was an early music mentor. Stan first introduced Eddie to music notation. Stan later recalled that Eddie had taken to writing music like "a duck to water."

Six-year old Eddie Sauter with drum, drum sticks at the ready.

Harvey Sartorius

As Eddie entered high school, his interest in music began to intensify. He began to study with Harvey Sartorius, a trumpet instructor who attended Columbia Teachers College. In addition to being Eddie's first significant instructor, Sartorius introduced him to a number of the city musicians so that young Sauter could start to play on sessions while still in high school.

Over two summers in high school, a family friend landed him a gig playing aboard two French cruise lines. These bands were small ensembles, with only three or four members. On both voyages, Sauter traveled with 26-year-old saxophonist Raymond Schaeffer. A cruise ship gig with bandmates a decade his senior was an indication of the advanced musical abilities Sauter possessed even while a young teenager.

Archie Bleyer

Following his cruise ship experience, Eddie took a correspondence course with Archie Bleyer, one of the most significant early jazz and dance band stock arrangers. The course with Bleyer led to Eddie getting gigs with the master arranger around 1932-34.

Orville Mayhood

Through saxophonist Billy Fisher, Eddie Sauter found his way to studying with Orville Mayhood who taught composition at New York University. He also scored for and conducted silent films. Of Mayhood Sauter remarked, "I wouldn't call him a martinet, but [he was] a very rigid instructor."

Louis Gruenberg

While in Chicago as an arranger with the Red Norvo orchestra, Sauter took the opportunity to resume his formal study of composition. he took lessons with Louis Gruenberg who headed the composition department at Chicago Musical College. Gruenberg was a Russian-born pianist/composer who scored for numerous operas and films throughout the Golden Age of cinema.

Twenty-five-year old Eddie Sauter during his Benny Goodman years.

Dr. Howard Murphy

Back in New York, Sauter took up lessons once again at Columbia Teachers College. This time his instructor was Dr. Howard Murphy, head of the music theory department at Columbia. Those lessons took place sometime between 1938 and 1939.

The lessons at Columbia Teachers College with Dr. Howard Murphy were not exactly what Sauter had been looking for and the arranger sought out the tutelage of some of the uptown Russian émigrés who had studied under Rimsky-Korsakov.

Bernard Wagenaar

Following this, Sauter began to study with Bernard Wagenaar at Juilliard without matriculating at the conservatory. Wagenaar, a composer and violinist, wrote mostly in a neoclassical fashion but incorporated some jazz elements into his work. Lessons with Wagenaar would be a presence in Sauter's ongoing musical education until around 1945.

Sauter reviewing a score with Ray McKinley.

Stefan Wolpe

In late 1945, Sauter began lessons with a man who was an incredibly significant contemporary classical composition instructor for many jazz composers: Stefan Wolpe (Vol-pea).

Born in 1902 in Berlin, Wolpe studied at the Klindworth-Scharwenka Conservatory and spent time interacting with the Dadaists at the Bauhaus. He studied the twelve-tone work of Arnold Schoenberg.

Allegedly, Sauter learned from Stefan Wolpe the practice of writing a chart and simply "putting it in the drawer," which may have accounted for his prolific output of music during his time with Ray McKinley. If there were ever a piece by Sauter during the McKinley period in which the influence of Stefan Wolpe can be heard, "Tumblebug" would be it.

Recalling his experience studying with Wolpe, Sauter explained that the time they spent together "opened up a whole world to me." He further elaborated on the precepts he gleaned from Wolpe, using some rather abstract terminology to indicate rather abstract concepts.

There was always a curiosity of "how does this work?" What Bartok and Stravinsky were doing in those days was not what I might have been used to hearing. It wasn't Wagner any longer; it was something else. And how that fit into the total thing fascinated me, and I did want to learn about it. I want(ed) to learn about Schoenberg. I've never gotten quite to Schoenberg. Twelve-tone never turned me on the way the other did. It still doesn't. But of course, Wolpe was a twelve-tone writer but what a good teacher; what an inspirational human being he was." — Eddie Sauter

Bill Finegan came out of the service and around the time Sauter was starting with McKinley, Sauter recommended to Finegan that he take lessons with Stefan Wolpe. Perhaps yet another reason Sauter and Finegan were such excellent collaborators.

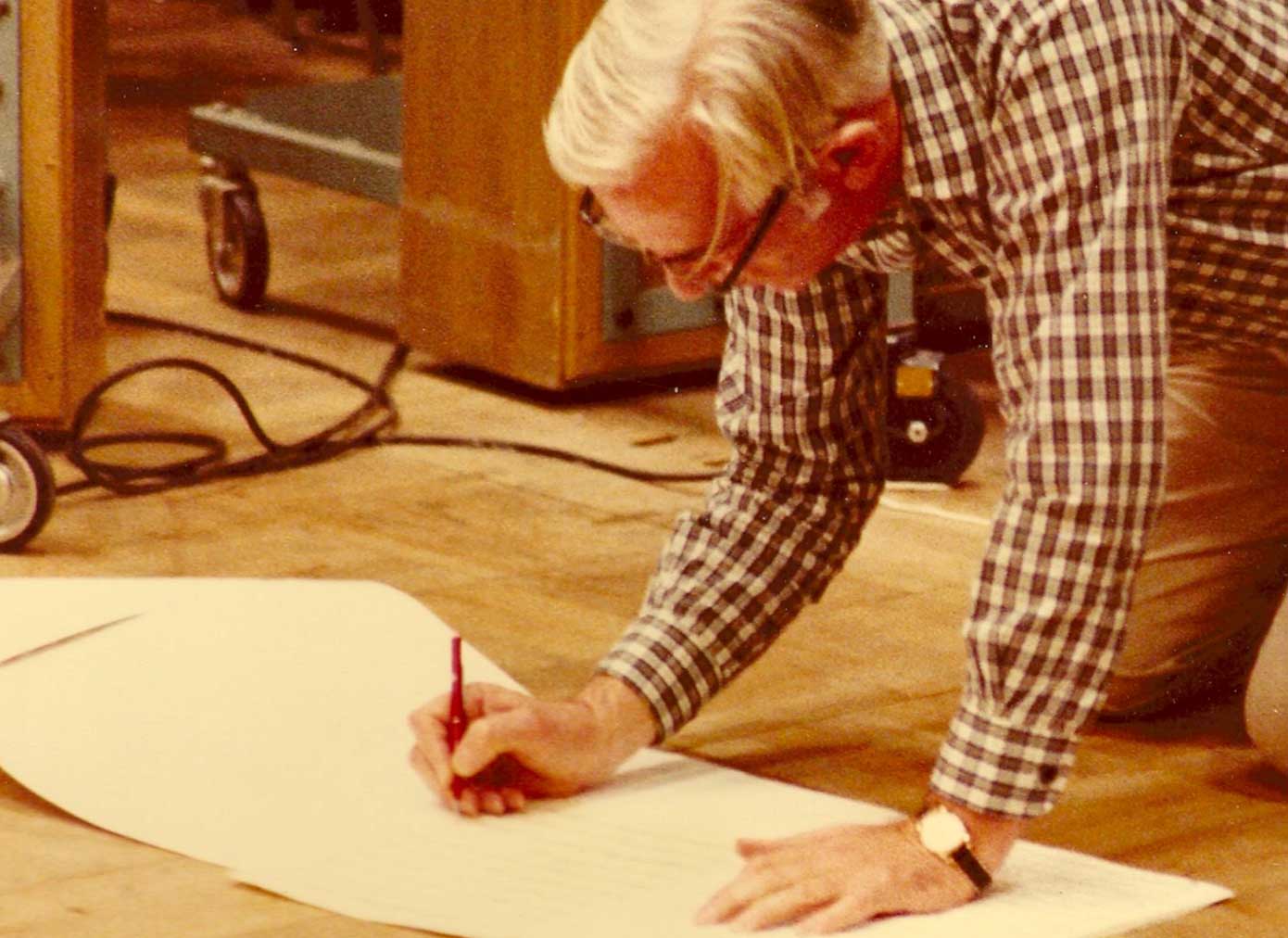

Sauter making score revisions for Night Gallery.

Meeting Bela Bartók

Many jazz historians believe that the two-note motif in the "I'm Late" movement in Sauter's masterwork Focus was an homage to Bela Bartók's second movement of Music for Percussion, Strings, and Celesta.

Sauter had the good fortune of meeting Bartók. During the meeting between Bartók and Eddie Sauter, Bartók was informed that Sauter was a young composer and his advice for Sauter was, "Young man, listen to Palestrina."

To Sauter, the experience was "like meeting God."

"Music 20 years ahead of its time." — George Simon, Metronome Magazine

"Every year that passes, Eddie Sauter's music becomes more important and somehow sounds even more fresh.

"His peers in writing for big bands all had their distinctive characteristics, but what separated Sauter's work from virtually all of them was the way that he integrated his specific musical language into the narrative structure of the music that he was arranging and/or composing." — Loren Schoenberg, Senior Scholar, The National Jazz Museum in Harlem